On the 250th anniversary of the publication of Common Sense and amidst an American crisis, it’s time to re-learn its lessons—and apply them

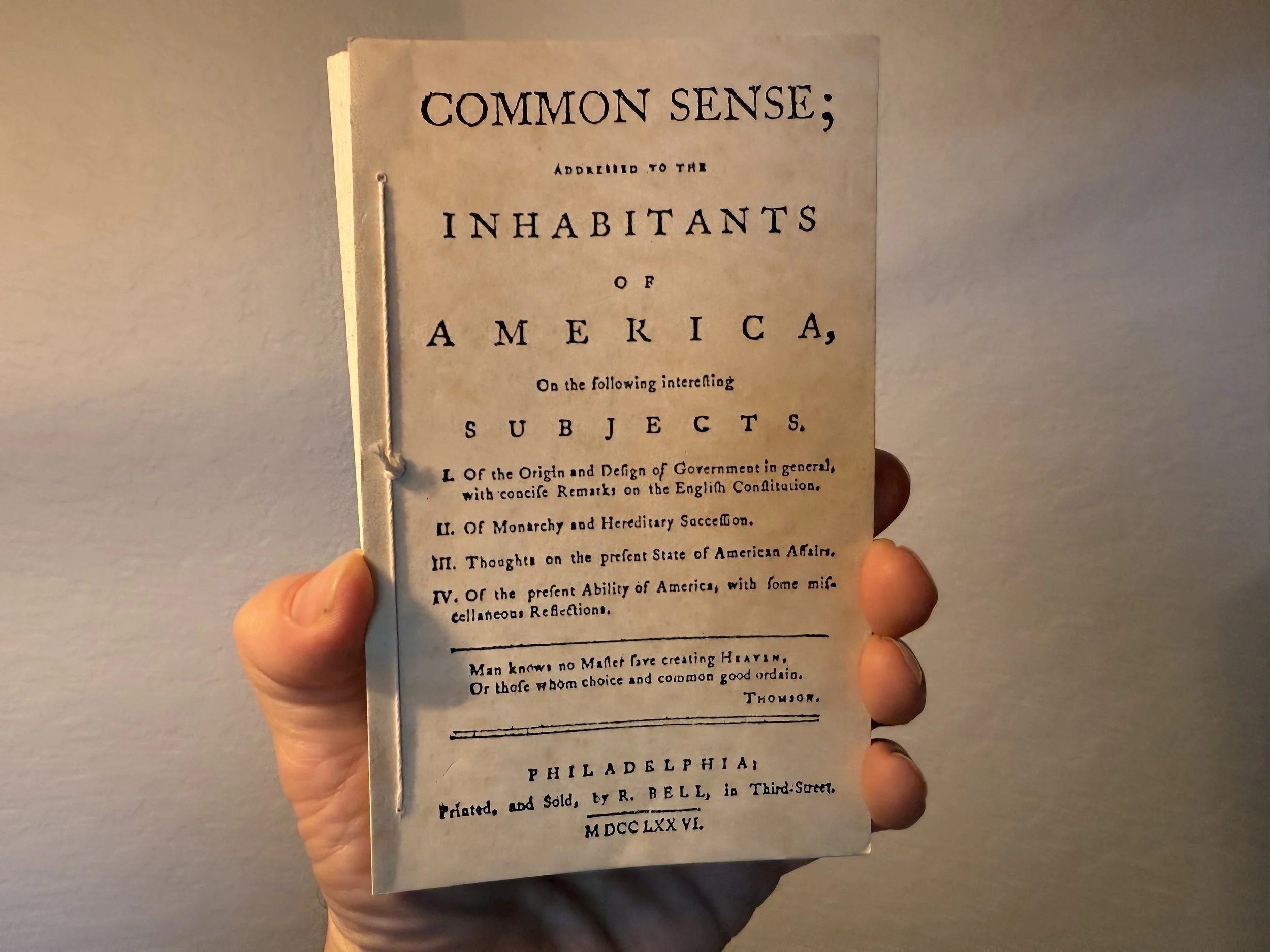

The author’s copy of Common Sense. (Photo: Author)

Jan. 10, 2026 by David Silverberg

Back in 2002, during a visit to Colonial Williamsburg, Va., I came across a shop selling a facsimile of the pamphlet Common Sense. I wanted to read it the way a colonial would have read it, in the same form.

That proved a bit challenging. There are s’s that look like f’s. It uses British spellings like the frequently-used word “honor” as “honour.” It’s full of old usages like the word “hath,” which evolved into today’s “has,” “doth,” which evolved into “does,” and “‘tis,” which evolved into “its.” At the bottom of each page is the first word of the next page, to guide the printer in the proper order. Still, for all that, it’s worth persisting.

It’s a small publication: my copy measures 4 and ¼ inches by 6 and ¾ inches (10.8 cm by 17.1 cm) and is 80 pages long, not including the covers. The first editions were between 47 and 50 pages.

This little pamphlet was published exactly 250 years ago on this day, January 10, 1776.

It proved to be an intellectual earthquake that birthed a new nation.

There is a story that the author, Thomas Paine, was so enthusiastic and excited upon receiving his printed copies that he opened up the window of his lodging and started throwing copies to people passing by in the street. The story has never been historically verified, but even if untrue, it should be true. Paine knew he had written an original and powerful work. As he foresaw, it went on to shake the American colonies and ultimately the world.

On this day 250 years later, Common Sense is as relevant—and as urgent—as it was on that other January day. Indeed, today Paine might have called it No Kings!

OF MONARCHY AND HEREDITARY SUCCESSION

In Common Sense, Paine set himself the task of convincing American colonists that they should create a separate, sovereign state independent of Britain.

His first task in doing this was to demolish the legitimacy and authority of monarchy, then ruling the colonies, as a form of government.

Paine was writing about the English monarchy but his arguments went much further: he opposed monarchy in its fullest sense: “mono,” Greek for “one” and “archy,” Greek for “power” or “authority.” He was against one-man rule of any kind.

Knowing his audience, Paine first drew on Biblical references to show that monarchy was not only anachronistic but profane.

“Government by kings was first introduced into the world by the Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom,” he wrote. “It was the most prosperous invention the Devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry. The Heathens paid divine honours to their deceased kings, and the Christian World hath improved on the plan by doing the same to their living ones. How impious is the title of sacred Majesty applied to a worm, who in the midst of his splendor is crumbling into dust!”

He recounted all the arguments over kingship when the ancient Hebrews debated whether to anoint a king but his main point was that worshipping a single man violates the scriptural covenant with God.

“And when a man seriously reflects on the idolatrous homage which is paid to the persons of kings, he need not wonder that the Almighty, ever jealous of his honour, should disapprove a form of government which so impiously invades the prerogative of Heaven.” Monarchy, he wrote “in every instance is the popery of government.”

He also had no use for hereditary succession, which, he wrote, was another evil that added the “degradation of ourselves” to “an insult and imposition” on future generations.

All men having been created equal, “no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever, and tho’ himself might deserve some decent degree of honours of his contemporaries, yet his descendants might be far too unworthy to inherit them.”

Ultimately, all kings—and autocrats of any kind—for all their pretensions, ultimately have humble, if not disgraceful, origins.

He put this in a way that strikes a very contemporary chord: “This is supposing the present race of kings in the world to have had an honorable origin: whereas it is more than probable, that, could we take off the dark covering of antiquity and trace them to their first rise, we should find the first of them nothing better than the principal ruffian of some restless gang, whose savage manners or pre-eminence in subtilty obtained him the title of chief among plunderers… .”

Kingship, monarchy and autocracy of any kind, he argued, “opens a door to the foolish, the wicked, and the improper, it hath in it the nature of oppression. Men who look upon themselves born to reign, and others to obey, soon grow insolent.” [Emphasis ours.]

What was more, hereditary monarchy didn’t ensure peace as its advocates argued; quite the contrary, as a form of government it opened the gates to wars foreign and civil and constant strife, he argued.

“In short, monarchy and succession have laid (not this or that kingdom only) but the world in blood and ashes. ‘Tis a form of government which the word of God bears testimony against, and blood will attend it.” And further, “Of more worth is one honest man to society, and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.”

The immigrant

Thomas Paine, as depicted circa 1792. (Art: Laurent Dabos/National Portrait Gallery, UK)

The person who penned these words was born in Thetford, Norfolk, England on Feb. 9, 1737 to a humble tenant farmer who also made stays, the ribbing in women’s corsets. His father, Joseph, was a Quaker and his mother Frances was Anglican.

Paine attended grammar school at a time when schooling was not legally required. He apprenticed as a staymaker to his father and mastered the craft but then left home to become a privateer—a credentialed pirate—at the age of 19. Once he returned home he took up staymaking and opened his own shop.

Before 1774 Paine’s life was a chronicle of tragedies and failures. His business went broke and his wife died in labor along with their child. He separated from his second wife. He held a variety of low-level government jobs, ran businesses that failed and taught school for a time.

After moving to Lewes in Sussex in 1768 he became involved in civic affairs and began his first political writing. However, his string of professional setbacks continued.

In 1774 Paine moved to London where he was introduced to Benjamin Franklin, the lobbyist representing the American colonies. Franklin suggested that Paine emigrate to America, specifically the colony of Pennsylvania, and provided Paine a letter of recommendation.

Paine took the suggestion and arrived in America on Nov. 30, 1774, so sick from the passage that Franklin’s doctor had to have him carried off the ship. It took him six weeks to convalesce but once he did, he took an oath of allegiance to the Pennsylvania colony and took up work as editor of Pennsylvania Magazine.

At 38 years of age, Paine had finally found his niche.

‘TIS TIME TO PART!

Having demolished the legitimacy of monarchy as a form of government and specifically a form of American government in Common Sense, Paine now had to urge Americans to seek independence and do it right then.

“Now is the seed-time of Continental union, faith and honour,” he argued. To put it off independence was to simply postpone an inevitable conflict to a future generation.

He rejected all prospects of reconciliation. The battles of Lexington and Concord had occurred the previous April 19 followed by the battle of Bunker Hill the previous June. “All plans, proposals, &c. prior to the nineteenth of April, i.e. to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacks of the last year; which tho’ proper then, are superceded and useless now.”

If they sought independence the colonies were not merely establishing a new nation, they were creating a new world full of promise, he argued: “The Sun never shined on a cause of greater worth,” he wrote. “‘Tis not the affair of a City, a County, a Province, or a Kingdom; but of a Continent—of at least one eighth part of the habitable Globe. ‘Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected even to the end of time, by the proceedings now.”

Then his pen fairly screamed off the page in what today would be an all-caps tweet: “Every thing that is right or reasonable pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ‘TIS TIME TO PART!”

Hints and suggestions

But if the king were overthrown and America was independent, what would follow?

Paine acknowledged the fear and uncertainty plaguing undecided Americans. “If there is any true cause of fear respecting independance, it is because no plan is yet laid down. Men do not see their way out,” he wrote.

He decided to “offer the following hints” and in answering this question Paine laid the intellectual groundwork, not only for the revolution that followed, but for the government that rose out of it. He has never been given the full credit due him for his role in creating the ideas that shaped the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights and the United States itself.

Writing later in the year in the Pennsylvania Evening Post, he proposed a name for the new country: “until, as other nations have done before us, we agree to call ourselves by some name, I shall rejoice to hear the title of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in order that we may be on a proper footing to negotiate a peace.”

That suggestion came to pass.

In Common Sense he suggested that the colonies explain themselves to the world: “Were a manifesto to be published, and despatched to foreign Courts, setting forth the miseries we have endured, and the peaceful methods which we have ineffectually used for redress; declaring at the same time, that not being able any longer to live happily or safely under the cruel disposition of the British Court, we had been driven to the necessity of breaking off all connections with her; at the same time, assuring all such Courts of our peaceable disposition towards them, and of our desire of entering into trade with them: such a memorial would produce more good effects to this Continent, than if a ship were freighted with petitions to Britain.”

That manifesto was published seven months later as the Declaration of Independence. Just as Paine suggested, it was addressed to “a candid world” and set forth the principles, reasons for separation and complaints of the new nation.

Paine may have had a hand in drafting or editing the Declaration since his initials appear on a draft. But when the Declaration was published in July, it was published at the back of the Pennsylvania Magazine that Paine edited as a special feature, a surprising place for such a monumental document. Still, that publication marked its first appearance in an American magazine and appeared at the same time as newspapers carrying it as breaking news.

In Common Sense Paine proposed creating districts in each colony and annual assemblies of delegates to a Continental Congress, with a rotating president. Indeed, along the lines of this suggestion, the colonies founded a Continental Congress, which evolved into the House of Representatives.

Paine’s use of the word “president” was notable. At the time “president,” meaning “one who presides” (literally, from the Latin, “praesidens,” derived from “prae” or “before” and “sedere,” “to sit”) was not a widely used honorific. Ultimately it would be adopted as the title of the nation’s chief executive.

He proposed “A Committee of twenty six members of congress, viz. Two for each Colony.” This became the Senate.

“The conferring members being met, let their business be to frame a Continental Charter, or Charter of the United Colonies; (answering to what is called the Magna Charta of England) fixing the number and manner of choosing Members of Congress, Members of Assembly, with their date of sitting; and drawing the line of business and jurisdiction between them: Always remembering, that our strength is Continental, not Provincial.”

This “Charter” came to fruition as the Constitution of the United States.

Then he addressed another big issue.

“But where, say some, is the King of America? I’ll tell you, friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Great Britain.”

When the Charter was adopted, Paine proposed: “let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the Charter; let it be brought forth placed on the Divine Law, the Word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other.”

Once the ceremony adopting the Charter was completed, Paine suggested that the ceremonial crown be taken down, smashed to pieces and the pieces distributed to the crowd, symbolizing NO KINGS!

An asylum for mankind

Paine fully understood that what could be created was entirely new.

“The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind,” he wrote. “…We have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest, purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” he wrote.

He also stood straightforwardly for freedom of religion, religious diversity and open immigration.

When he suggested the Charter he argued that it should be “Securing freedom and property to all men, and above all things, the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience… .”

He went further in advocating “liberal” religious “diversity,” specifically using those terms: “For myself, I fully and conscientiously believe, that it is the will of the Almighty that there should be a diversity of religious opinions among us. It affords a larger field for our Christian kindness: were we all of one way of thinking, our religious dispositions would want matter for probation; and on this liberal principle I look on the various denominations among us, to be like children of the same family, differing only in what is called their Christian names.”

Those ideas went on to be embodied in the Bill of Rights and the first sentence of the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof… .”

What is more, he saw America as a haven such as the world had never before known and he put it in passionate and emotional terms: “O! ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the Globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her. Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.”

As Paine conceived it, that was what America was founded to be; a haven and asylum for those seeking free faith and freedom.

Bestseller and author

A statue in Burnham Park, Morristown, NJ, of Thomas Paine writing the pamphlet “The Crisis” on a drumhead. (Photo: Diane Durante, used with permission)

Common Sense was a viral hit.

Paine estimated that it sold 100,000 copies. That would have been in a colonial population of about 2 million. Its sales may have been much higher and there were likely many unauthorized editions. It took pride of place next to the Bible in colonial homes. It was read aloud in taverns and at public meetings. It may very well be the bestselling American publication of all time and certainly the most widely circulated.

Paine deliberately kept his name off the publication, according to one telling, because he feared retaliation by the English government. However, as he put it in a note in the third edition: “Who the Author of this Production is, is wholly unnecessary to the Public, as the Object for Attention is the Doctrine itself, not the Man.”

Paine donated his proceeds to the Continental Army, which he joined after independence was declared.

During the conflict Paine marched with the troops and penned a series of pamphlets called “The American Crisis.” It was during the darkest days of the Revolution at the end of 1776 after defeats in New York that he sat down, writing on a drumhead according to legend, and penned what would become what was probably the most famous paragraph he ever wrote, starting with the words, “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

In 1777 Paine was named secretary to the Congressional Committee on Foreign Affairs but clashed with the leadership and resigned. He was sent on a fundraising mission to France, where he worked with Benjamin Franklin, and then traveled to other countries in Europe to raise funds.

After the revolution Paine traveled back and forth from America to Britain, writing and pamphleteering the whole time.

As the French revolution broke out he became a passionate advocate for French republicanism, writing the tract Rights of Man in 1791 to counter Edmund Burke’s anti-revolutionary Reflections on the Revolution in France. He was granted honorary French citizenship and elected a member of the National Convention although he didn’t speak French.

As passionately republican though he was, Paine was a moderate in the spectrum of French politics and opposed execution of King Louis XVI. When radicals took over and initiated the reign of terror, Paine was imprisoned.

The story is that he was sentenced to be guillotined. However, the night before executions jailers would mark the cell doors of the condemned with chalk. Paine got the chalk mark but because the door was open, it was on the inside of the door and was overlooked the next morning.

A deliberate mistake? No one will ever know for sure but Paine was spared. He was released and readmitted to the Convention after the radicals fell.

Paine kept writing and pamphleteering, ever independent and contrarian. He advocated a French invasion of England and overthrow of the king, opposed Napoleon Bonaparte as “a charlatan,” attacked George Washington for not coming to his aid during his imprisonment and called him treacherous, hypocritical and unworthy of his fame.

He returned to America in 1802 on the invitation of President Thomas Jefferson and published The Age of Reason, submitting religious faith to his searching and intense logic.

“I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life,” he wrote. “I believe in the equality of man; and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavoring to make our fellow-creatures happy.”

It was widely read but also widely condemned.

Paine died in New York City at the age of 72 on June 8, 1809. Only six mourners came to his funeral, two of them black freedmen honoring his consistent opposition to slavery. Quakers would not allow him to be buried in the cemetery he requested and the location of his bones—if they still exist—are unknown today.

Thomas Paine’s death mask. (Photo: WikiMedia Commons)

Legacy, relevance—and immediacy

When he started writing Common Sense, Paine had only two tools at his disposal: language and logic.

He was just another immigrant to America, someone unremarkable and ordinary in daily life, in no way prepossessing or outstanding. His greatest asset was the letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin. Otherwise, he had nothing.

But he was caught up in the spirit of America and it inspired him to express his thoughts. He could not know if his ideas would meet public approval or even be noticed. Still, the concept of starting anew, of a continent full of potential, of creating something better, of righting wrongs and seeking freedom were so inspiring that he made the effort.

That effort and the pamphlet it produced created the intellectual framework for the American revolution. But more, it created a mindset and outlook and birthed fundamental principles that molded American thinking and behavior that have lasted 250 years.

Until now.

The Enlightenment ideas in Common Sense were attacked when they were published. They have been under threat ever since. In the 20th century they came under attack from European Fascism. But those ideas inspired defiance and resistance. Ultimately, they triumphed with the democracies and went on win over a part of the world that called itself “free.” With the fall of the Soviet Union they swept the part of the world that had been under the Communist heel and went on to spark color revolutions and the Arab Spring.

Today the ideas of Paine and Common Sense are under attack in the country whose birth they inspired and by a president whose office Paine conceived.

They are threatened by a man who sees himself as king, one who is most “foolish,” “wicked,” and “improper” as Paine warned.

All of Paine’s admonitions against the concentration of power in a single man’s hands, about elevating one person high above other people, about immunity from the law, about the potential for insolence, corruption and arrogance, are suddenly blazing anew in the person of Donald Trump.

What is more, they are under direct physical attack. The killing of Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis at the hands of masked and unaccountable agents and long before her, the death of Heather Heyer in Charlottesville, Va., at the hands of a neo-Nazi, are attacks on Common Sense and its ideas of law, justice and democracy. As Paine would have put it, “the blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature” cries out for redress.

But Paine also understood that in addition to revolt and resistance, freedom required friendship and cooperation among all people of like mind. He put this very well in Common Sense.

“WHEREFORE, instead of gazing at each other with suspicious or doubtful curiosity, let each of us hold out to his neighbor the hearty hand of friendship, and unite in drawing a line, which, like an act of oblivion, shall bury in forgetfulness every former dissention. Let the names of Whig and Tory be extinct; and let none other be heard among us, than those of a good citizen; an open and resolute friend; and a virtuous supporter of the RIGHTS of MANKIND, and of the FREE AND INDEPENDANT STATES OF AMERICA.”

But as he learned—and as Americans are learning now—good intentions are not enough. Today, at a time of duress as acute as that 250 years ago, it makes sense to draw on Paine’s wisdom written in the cold and misery of failure and crisis. It’s his most famous paragraph and one that sheds light in even the darkest times, and one so immediate that it might have been written this morning. But as it did then, today it provides inspiration to persist and look to the dawn of the day after tomorrow.

“THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.”

Art: Dennis Goris

To read and download a full PDF of Common Sense from Google Books, click below.

Liberty lives in light

© 2026 by David Silverberg